Rhythmic gymnastics is a beautiful sport that combines flexibility, strength, elegance, coordination, and work with apparatus together in a perfect harmony with music. It’s so complex though, it becomes very difficult sometimes to find the right balance of all the components needed in training to achieve this ideal effortlessness in our gymnasts’ execution. We’re training for grace and power at the same time in order to create something spectacular, however, combining these 2 elements of training can be quite tricky – so what’s the right amount of each, how to incorporate them into training, which exercises to use, and when? Let’s start at the beginning..

How flexible is too flexible?

As discriminatory as it may sound, if a girl wants to be a world-class rhythmic gymnast, she needs to be naturally gifted. There is a condition called hypermobility, as most of you probably know, which is generally understood as a disorder of loose joints and/or increased connective tissue laxity (muscles, ligaments, joints, tendons, but also the heart muscle, or digestive tract) (3). If you read about it, it may quite frankly scare you and be a reason for you not to enroll your daughter into gymnastics. Don’t be so quick to judge though. Although hypermobility can pose a risk for developing health problems later in life, it very much depends on the type and severity you have. Hypermobility is genetic and is mostly caused by differences in collagen, thus making the tissue around joints looser, such as in Ehler’s Danlos syndrome (1), but, as the source states, it can also be due to a different “shape of the ends of your bones.” It is associated with a range of symptoms, such as pain and/or stiffness of the joints, tiredness, frequent sports injuries (1), but also seemingly non-related ones like anxiety (4), headaches, heart palpitations, thin skin, or constipation (1). Most of the hypermobility syndrome is benign, meaning it occurs but doesn’t necessarily negatively impact your life. That’s why it is important to realize that even if you’re diagnosed with hypermobility, it doesn’t automatically mean you can’t do sports; on the contrary, the more you strengthen your muscles, the less likely you are to develop any further problems. While there might be some risks of injury associated with hypermobility, as studies suggest, it is only correlated with those few affected joints, while in people with overall low flexibility there is a higher risk of injury in all the joints (6). Furthermore, some studies have found no correlation between hypermobility and injury at all; others state that male athletes with hypermobility are more prone to injury (4). Most of the male studies are also conducted using male athletes playing contact sports where the risk of injury itself must be bigger so maybe male dancers wouldn’t be affected by injuries as much… Nevertheless, if you do notice any of the symptoms stated above, especially if there’s a family history of hypermobility, it’s a good idea to get it checked before your child starts any sports activity.

Are you hypermobile?

One test you can easily do at home to test for hypermobility is an old classic called Beighton’s score which gives you 5 exercises to test your mobility and each one is worth a point (for 2 through 5 give yourself 1 point for each side). 1-standing forward fold with both palms on the floor, 2-hyperextension of each knee over 10°, 3-overextension of each elbow over 10°, 4-touching your forearm with your thumb, 5-flexing all 5 fingers back over 90° or your pinkie just to 90°. A score of 5 or more (in women) is supposed to give you an indication of a possible hypermobility syndrome; however, evidently, it has had very inconsistent results and is not being used as often nowadays (4). Why not try it at home though, at least for fun? For me, personally, the test score is 3 – I can do the forward fold with hands on the floor and I also have hyperextended elbows, BUT, according to the most classic test out there, I shouldn’t be considered hypermobile. That should be a good thing (although maybe not for a gymnast) but all my doctors always write “hypermobile” into my charts even though they know the flexibility might be acquired through sport. Just to be clear, I’m not saying all my flexibility is taught – I have always had loose hip joints, overextended elbows, and probably some more flexibility in my lower back than average people, but that’s not nearly impressive for a rhythmic gymnast.

What do we look for?

As a coach, I also look for flexible upper back, a little hyperextended knees, and very importantly, the arch in gymnasts’ feet. In rhythmic gymnastics, what we actually want are shallow hip sockets (when hip joints are positioned a little further away from the pelvis so that they can achieve a larger range of motion) or a higher angle between the thigh bone and the end of a hip joint, as well as flexible thoracic and lumbar spine which is mostly due to the vertebrae being further apart from each other. Years back, I’ve seen a documentary about ballet where the ballet teachers stripped the kids applying for a spot in their academy into their underwear so that they could properly try out their hip turnout and examine their natural ballet ability. I thought it was a thing of the past but just recently I’ve clicked through some videos on YouTube and found a podcast between Maria Khoreva and Claudia Dean about differences in ballet schools in London and St.Petersburg and was quite surprised to hear the same old story (7). Evidently, in Russia, they are taking the art of ballet and probably also any kind of sport very seriously and are only willing to work with children who have the biggest potential to represent their country in the best light. While it is absolutely understandable, it just shows how much pride they carry towards their country and frankly, don’t seem to care about individuals as much as we do. Naturally, I used to be very achievement-oriented in the beginning of my career too but now I am slowly progressing to a more “caring” approach because the satisfaction of seeing a little kid progress at any pace is just bigger than any medal.

To get back on the topic, in Caucasians or “white people” the prevalence of benign hypermobility without any other symptoms is between 5 and 18% but up to 43% everywhere else (3) which puts us in quite a disadvantageous position and at the same time sheds some light on why Russians are so much better (well, if we don’t count their nationalism and overall hard-working mentality, the fact that rhythmic gymnastics is much more popular and government-subsidized there, and the sheer population of potential gymnasts that exceeds our country 26 times…) :D It may also be interesting to note that women are twice as likely to be hypermobile (3) since it might be another big reason why rhythmic gymnastics, contortion, or even dance are more popular amongst women than men.

How to improve flexibility?

I’m sure you’ve come across a crying child in a rhythmic gymnastics gym. Personally, I wasn’t one of them. I’ve gotten my splits in 2 weeks because of 2 reasons – I was naturally flexible so my starting point was a little better and it probably didn’t hurt as much, BUT MORE IMPORTANTLY, I just really tried hard. I kept pushing myself into the splits all the time until I got them and never really perceived it as pain. That’s why when I came across these kids who cried at every practice as a coach, I felt like they were just being overly sensitive and didn’t understand that cliché quote “no pain, no gain.” Over the years, however, I’ve had the opportunity to work with a huge variety of children of varying levels and it led me to a definitive conclusion that physical predisposition actually matters A LOT. Though it might be discouraging for some, neither of us is perfect for every sport and sometimes you just have to accept that hard work doesn’t always beat talent, in spite of what we’d like to believe. Rhythmic gymnastics, at least the professional one, is reserved for the few special gifted ones.

Nevertheless, there are ways to improve one’s flexibility to the maximum potential of one’s body; it’s just going to take some time. Therefore it is important to explain to young gymnasts that they should be stretching to the point where it pulls but doesn’t really hurt or sting which could be a sign of muscle / tendon overstretch or tear. Although it is a myth that muscles lengthen when stretched, it WILL stop hurting after some time. The reason is actually very simple – you literally get used to the pain. The science behind it is that when a muscle is stretched, its receptors perceive it as a threat and start signaling you pain. This sensation, however, can only last so long and because you are going against the pain voluntarily, this “autogenic inhibition reflex” gets tired and the muscle relaxes. When static stretching is repeated regularly, especially for prolonged periods of time (e.g. 5 min in an oversplit, as we all do), you just get used to the feeling and don’t perceive it as pain anymore (2). The key phrase is “prolonged periods of time,” as Mrs. Marie Moltubakk, a world-class brevet RG judge from Norway explains in her dissertation thesis titled “Effects of long-term stretching training on muscle-tendon morphology, mechanics, and function” (5). I’ve found a video of Moltubakk’s dissertation presentation on YouTube through her social media and was very pleased that someone other than Russians is actually trying to bring some science into rhythmic gymnastics (because it’s not that easy to research in Russian at my current level). She explains that based on the studies she’s reviewed and her own research experiments; the optimal stretching for a rhythmic gymnast (a program that creates the best results in the shortest period of time) is 1-5 min for 1 exercise a day of static stretching regardless of whether you do the whole load at once or divide it into reps. There’s a general consensus that to see results, consistency is key, however, some studies show that if you maintain the required volume, 2 days a week can possibly be just as effective. From my own experience, when starting at a young age, the best strategy is to start with shorter but frequent sessions, which usually means 60 min 3 times a week, first holding the splits for 30s and slowly increasing. It is very important to realize that more isn’t always better and with flexibility we need to be patient. Some kids will need months to get their splits and pushing them to go harder until they cry from pain will only make them resistant to stretching, both mentally and physically. There is actually one study that shows there is no difference in long-term stretching goals achievements between those who stretched super-hard to the point of pain and those who only stretched with low intensity. For dynamic stretching, the recommendations are 5-10 repetitions per exercise and lots of different changes in positions which is pretty common in RG (think of all the kicks on the floor, by a bar or during jumps/leaps section of the training). Another well-known method of stretching is called PNF or “Contract - relax - stretch,” which works on the basis of pulling the muscle to the maximum ROM / range of motion, contracting it there - either against a coach’s hand or to an even bigger ROM for a few seconds, and then either relaxing or passively stretching further. The premise of this method used to be to “relax the muscle even further,” which allegedly has been proven wrong (6), however, the mechanism still works as it stretches and strengthens the muscles at the same time. I have been using this type of stretching primarily with splits to get girls to activate their muscles more during an oversplit from 2 chairs – pulling themselves up, holding it there for a second, and relaxing to the maximum ROM for 10 repetitions at the end of a passive stretch. This technique has proven effective in not only helping to achieve a deeper stretch but also strengthening the hip flexors and thighs while forcing the gymnasts to keep their hips square and engaging the muscles they’ll need later when doing e.g. penché balances or split leaps.

With back flexibility, it’s a little more problematic because while we want the hypermobile girls who can put their head on their butt without warm-up, we also need to make sure that we don’t wear out their spines. In the lumbar region there is great capacity for flexibility which is convenient but also creates problems because we tend to put too much pressure on this part of gymnasts’ spines. Naturally, most people will be able to do the “cobra” yogi position where you press up from the ground and lift your torso while lying on your stomach with hips on the floor. What we require from little kids as one of the first gymnastics exercises is to then bend their knees and put their toes on their head. Most kids will do the exercise by pushing their stomach further from the ground – putting lots of pressure to the lumbar spine while neglecting the thoracic. It is to be expected since it’s the easier way to get to the pose, similarly to when kids really want to do the splits so they push their groin to the ground in an absolutely crooked way to see the results faster. We as coaches should never encourage this behavior but rather require correct technique with longer but steady progress and smaller risk of injury. Vertebrae in one’s spine aren’t working the same as hip joints. There are 24 of them with only small spaces in between that can create some amount of flexibility, and the way we use them isn’t by elongating the small muscles around them but strengthening them and using shoulder and hip flexor mobility to increase the range of motion (6). Therefore, while stretching the back, we should focus more on the upper part – correcting the posture and strengthening the muscles around the spine, again, rather than pushing through pain into neck-breaking positions; and when a gymnast doesn’t have a flexible back, we need to make sure to work on her hip and shoulder flexibility to be used as a compensation for elements like a ring balance or a back scale.

In Moltubakk’s webinar from September 2020 where she also dives into her research, we can see a chart depicting all the factors influencing flexibility, such as age, sex, or joint structures that unchangingly determine one’s level of flexibility but also external factors that, besides creating a systematic training program can also be of help in our quest for more and more flexibility. Factors like temperature or “psychosocial setting” can be influenced super easily though, which is something that coaches often forget about (6). Myself, I’ve had really good results with gymnasts who are naturally tight (you know, those who go for a week-long vacation and come back without basic splits) when they stretched every other night after a warm shower because the muscles were much more relaxed than in our old stonewall gym hall that gets cold even in the summer. That’s also why I always wear a back-warmer and leg-warmers most of the year and recommend the same to all of my gymnasts. You only have one back and one Achille’s on each leg so it’s only rational to protect them from getting injured when you know you’re overusing them every day. There are only a few good options for back-warmers that have the right ratio of materials to ensure that your back stays warm and dry even if you get sweaty so be careful not to choose a piece of double-layered cotton sewn together and sold for 20€. My personal favorite is Sasaki HW 8043 made of acryl, rayon, and polyurethane (8) and the old classic white one from any local medical supplies store made of wool, acryl, polyamide, and elastane (9) which is also half the price, by the way. Apart from the temperature, the other non-traditional thing you can influence is the way your gymnasts feel about stretching mentally. If you leave them in overspilts for 5 minutes and threaten them with additional minute if they try to fix their position, the only result you’ll get is them hating splits and feeling stressed which can, in return, tighten their muscles even more. What I stand for is having a conversation with them during this time and use it for 2 effects – 1st - getting to know them better which strengthens our coach-gymnast bond and shows them that I actually care about them, and 2nd- distracts them from pain. Interestingly, I know for a fact that a lot of older coaches wouldn’t agree with me because their view is that authority comes from fear and power, however, it is odd to me that this kind of thinking still persists at this day and age. My perspective is, gymnasts should feel supported by their coaches and that is not going to happen if they fear them. Respect should be deserved, not forced.

Should coaches stretch their gymnasts?

Been there, done that. Was it right? That’s a complex question. First, we need to acknowledge that stretching legs and back is very different, although you can certainly hurt your gymnast either way. In my 12 years of experience, I have seen several injuries by coaches in both cases, even one broken bone. Quite fortunately for the club, the gymnast’s parents were never angry because they understood that it’s a part of the sport (and we’re not in the US, we don’t sue people here for anything, really). The problem is, it IS a part of the sport but only because most coaches are still more focused on fast results without regard for their gymnasts’ well-being and it’s just generally accepted as a norm. When I was an active gymnast, all my coaches would sit on my back while I was in a “cat” position and stretched my shoulders backwards / the same lying on the stomach and arching my back, they would sit on my hips in a “frog” position and push us down in oversplits by their own weight, and sometimes they would encourage us to sit on each other’s toes or knees with heels put on a higher surface. Reading it now in 2021, it seems crazy to me that I considered that normal. However, I started doing the same my first years as a coach since that was what I knew and what I saw repeatedly by all the coaches from all the countries I have encountered on competitions and in videos online. One of these stretches that was quite popular for a long time was taking a girl’s heel when she’s kneeling and stretching it towards her head, then pushing her hip forward with our knee into an oversplit. Every gymnast was just OK with it and it was a part of our regular practice. On time, a girl came back to training after a ski trip and couldn’t do the splits anymore so I did this stretch, quite lightly, but she started pushing against the force and ended up with a muscle strain which left her in disadvantage for that season because of the required rest time. I was really worried that time and even though I knew I hadn’t directly caused her an injury (and it wasn’t anything serious, thank God), I couldn’t shake the feeling that it was unnecessary.

Gradually, I stopped stretching my gymnasts, for a few more reasons. When I started working with recreational groups, most often than not, these girls just didn’t have that drive that would make them go over their limits and forget the pain. It didn’t make them feel stronger and more capable like it makes me, they just lost interest. Next, I have observed that most little kids are just unable to process the concept you’re asking them to accept when you tell them not to push against you because they will hurt themselves. They just feel it hurts and don’t think any further. Hence, you have to “surrender” and rather explain how to stretch the right way. You can show them your perfect oversplit and skyrocket their motivation, especially when they’re still little and admire your abilities. You can show them on other girls and kill 2 birds with 1 stone when they feel a flick of motivation for being a good example; and you can show them videos from competitions so that they can see what is possible with a little bit of determination and a strong will. Partner-stretching, however, hasn’t magically disappeared because I decided to wipe it out of this world and so every now and then I come across it in a tutorial or hear a physical therapist criticize it in a webinar. Therefore it is vital to know..

How not to hurt yourself (or your gymnast):

- Technique - first and foremost!

Since we’ve established that stretching your gymnasts as a coach may be risky, the whole work is on them now and you are the one to make sure your gymnasts perform the exercises correctly. Don’t let them slide into the “more is more” mindset where they’ll stretch against constant lower back pain or twist their bodies to one side just to get the element at a cost of their own health. I know I’m not the only one with scoliosis but I’d love to be the last one. To add to that, you are not only protecting their bodies but building a good basis for the more difficult elements that can’t be “faked.” As I always tell them, “always stretch BOTH SIDES” alongside with “take me as a scary example.”

- Go slow

When you stretch, you need to take into account your overall physical abilities and your current physical condition. If you are just starting, stretch less intensely but frequently and if you are getting back to practice after sickness or vacation, maybe don’t go 100% just yet. On the contrary of what everybody is saying, you DO have time and if you use it wisely, you’ll last much longer than those “instant wonder” kids who reach their full potential at 12 years old and deteriorate.

- Be careful with your back

Your hamstrings and hip flexors can sustain a lot of pressure and only very rarely get overstretched but back is a whole another story. As Mrs. Moltubakk warns, you “should not use gravity” (6) or do “explosive movements” because when you stretch to your spine’s limit, your vertebrae touch and rub against each other which alone can wear them out. Now imagine what happens when you forcefully bend back with a lot of power – you can end up with a broken vertebra (spondylolysis) or a vertebra shifted outside of its place (spondylolysthesis) (10). It goes without saying that playing around with spine partner stretches is no joke. You should always go only as far as it feels semi-comfortable and stretch yourself because you know your body the best. Also, just a reminder, it’s OK to crack your joints as long as it doesn’t hurt. The cracking sound is created by gas bubbles in synovial fluid in your joints which burst when you pull the bones apart and several studies have now concluded it is harmless (11).

Regarding any chronic issues, since there is very little research done on rhythmic gymnastics possibly having a long-term negative impact on spine, we can only make judgments based on our experience and the former gymnasts’ statements. From my perspective it seems that those who are naturally flexible go through years of training without any significant injuries, just occasional pain from overworking their muscles. On the other hand, girls with less natural mobility will very likely try to achieve the same range of motion which will consequently put too much pressure on their vertebrae (or hip joints for that matter) and create a problem later in life. The same message of “better not overdo it” is screaming out of the pages of the paper I found targeted at contortionists. There were only 5 subjects from a circus school in Mongolia who underwent MRI scans with very concerning results of 3 limbus fractures in thoracic and lumbar spine as well as slight scoliosis and 3 bulging discs in lumbar area. They also found disc degeneration occurring in the older participants (who were 20-49 years old). Their spines were shockingly straight as opposed to a normal spine which is supposed to be curved as a letter S (18). There are several problems with this observation study – especially small sample size and very little variance as all of them were from the same school which could easily bias the results. If they all have the same coach or the same training plan, there is a high probability that the type of training is directly impacting their spines. It could be the training load that is very possibly insanely high, as is expected from an Asian culture; and it is also possible that these degenerative changes and injuries result from their innate anatomy. However, there is a good chance that prolonged extreme flexibility training can be a culprit here and we can’t ignore that. That’s why “go over your limit” maybe isn’t the best motivational speech you should give your gymnasts and should be changed to “do your best according to your abilities.” That’s why if suspect anything might be wrong with your gymnast’s back – especially if she’s complaining of persisting back pain that doesn’t go away with rest after practice, you should refer her to an orthopedist or a physical therapist to get checked out. Don’t underestimate any kind of symptoms and wait till it’s too late.

- Strength training before anything else

With extreme flexibility constantly on our minds thanks to the nature of our sport (and Instagram feed filled with 5-year-old Russian girls in 270° oversplits), sometimes we may shift the training ratio a little bit more towards stretching rather than work on the technique and strength. Although we justifiably need it for performance, I think it’s obvious that this is not the way to go. With too much flexibility and not enough strength we’re not only risking injuries (yes, I’m saying it again) but also compromising our gymnasts’ execution. Teaching them the right body posture, activating deep stabilizing muscles, and performing the body shapes through strength – not flexibility should be our ultimate goal. You can only build on strong foundation.

- THE CORE

The CORE message of this paragraph is creating a system that makes sense – a plan that will develop your gymnasts all the way, in all directions. In regard to perfecting the correct body shapes, maybe we should take artistic gymnastics training as a good example. They have established a whole system of partial exercises and progressions which beautifully build on one another and gradually create an overall capable gymnast. What we do instead is see what the particular child’s strengths and weaknesses are and only strengthen the already good. This way, we can achieve amazing results in a shorter period of time but will never reach her full potential. Unfortunately, I haven’t come across a fully developed RG training program yet. Therefore all of us are left to our own means which usually consist of taking what we’ve learned as kids, exercises we find online and through seminars, and the ones we’ve developed during our experience with real gymnasts, combining them together, and seeing what works. During this process, we use not only pure gymnastics exercises but all kinds of fitness workout plans which have proven to be effective in strengthening the core muscles which is primarily what everybody needs – so if you are a gymnast reading this and having a hard time doing the same boring exercises all the time, go online and find a pilates workout, ballet, or a callanetics one, and make your own routine for home so that you can keep yourself fit during lockdown. I guarantee you’ll see results in your gymnastics practice because all of the workout systems above are aimed at the deep stabilizing muscles which control your balance and keep your spine “at the right place.” Now’s the time to perfect the basics so let’s use this as an opportunity to improve our overall health and performance – hopefully, we won’t get another “chance” like this.

Strength vs. flexibility

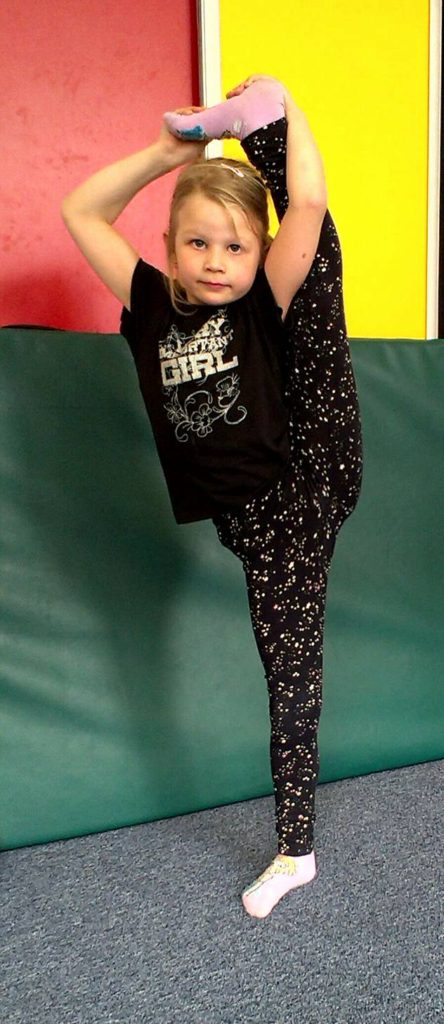

Now we can finally get into the good old myth section. First of all, have you ever seen a rhythmic gymnastics routine, like at a competition or online? If so, how is it possible that so many people still believe that flexible people are not strong? What have I missed? What about contortionists, The Chinese circus, acrobatic gymnastics, or even contemporary dance? Strength and extreme flexibility go hand in hand in these sports and activities. Check out Stefanie Millinger – the Austrian extreme adrenaline performer who climbs mountains and then balances in a contortionist handstand at the very edge of cliff, or hangs over a valley without any safety net or ropes - just enjoying the moment. When I first came across Milli, I have seen one of these stunts on her Instagram and my heart starting beating in an anxiety mode. I couldn’t believe she’s risking it (plus, you never know what’s real on the Internet nowadays) so I did some digging and found out she really does risk her life every time she creates a new video. People in the comment section were arguing that she’s been doing it for her whole life so for her it’s like for regular people to stand on their feet – but would you step on the edge of a cliff ON YOUR FEET? At this age, I probably wouldn’t even crawl – and I’m not afraid of heights and all for adventure. I am fully aware it’s a lot about her state of mind and focus but without enough strength she just couldn’t do this. The thing is, she’s super strong, while really skinny and extremely flexible (she can put her butt on her head in a handstand and also do some crazy oversplits) and people just can’t wrap their heads around it.

To give you a very specific example since we are talking about rhythmic gymnastics, recently there have been a video released on the Olympics YouTube channel of Ekaterina Selezneva being a subject to the scientific series of Olympic athletes put to the test to see what differences there are between particular sports and what is the general fitness level of a world-class athlete. The series called “Anatomy of an Olympian,” in this case, a rhythmic gymnast, uses a battery of tests including VO2max screening, leg power / jumping ability, endurance, etc. Besides the athletic testing, they also measured her body composition which showed only 9% body fat, a very low score for a female, even if she’s a high-level athlete. This makes sense though since she’s practicing twice a day so she inevitably develops this physique through training, but it also gives her a better probable outcome in regard for injury prevention. Her highest jump without help of momentum with her arms was 30cm, as compared to an average female score of 20cm. In the Wingate test measuring explosive power by making her ride a stationary bike for 30 seconds at maximum capacity against resistance, she peaked at 686W, with lowest score at 449W (12). The interesting thing is that although her scores were above average compared to general female population, they weren’t that high in comparison to other Olympic sports. What gives her an edge is the ability to maintain the force for a prolonged period of time, as the Wingate test presented. Ekaterina scored a “fatigue index” of 34% meaning that her power stays higher longer. It is an important take away because in rhythmic gymnastics, you need to be able to sustain that power during your whole routine and perform with grace and elegance without losing your breath and this experiment shows exactly that.

How to be strong AND flexible

As endurance is certainly important for a rhythmic gymnast, the question I get asked much more often is how to increase flexibility without losing strength (or vice versa) and whether it is even possible. It is amazing how many people who live their everyday lives surrounded by gymnasts and dancers still doubt the possibility of getting strong and flexible at the same time. It may seem contradictory to expect a very dynamic switch split leap from a hypermobile child but it is purely an assumption. If all the real-life examples you’ve seen so far aren’t enough for you, let me present some data on this topic. One largely Brazilian study from 2015 was conducted through an experiment designed in a way that provides answers for this exact dilemma. The researchers wanted to know how strength and flexibility training affected each other so they gathered athletic women in their 40s, divided them into 4 groups, and gave each group a different training plan lasting for 12 weeks. They were either doing only dynamic stretching, only strength training, or combination of both (stretching before strength training or after). The results showed that although all the groups increased strength (even the flexibility-only group), there was a significant difference in strength between the stretching-only and strength-only group at the end of the experiment (no surprise there). The stretching-only group and the stretching + strength group gained more flexibility as opposed to strength-only and strength + stretching group who gained more strength (13). These results are what we would expect, however, the differences are so small that it’d be foolish to argue that strength and flexibility rule each other out. What is interesting though is that all the groups in this study increased their flexibility, even the group that only strength-trained. Easy quick conclusion – don’t be afraid to do more strength training, it won’t hurt your flexibility; it can only improve the overall performance.

On the other side of the argument, there are studies to show that stretching training won’t hurt your strength either. The review article by sports scientists in Frontiers in Physiology from 2019 (14) examines this misconception by analysing 55 studies regarding the issue and sheds some light on the myth itself. The reason for so much confusion around the topic is that the notion that stretching decreases strength isn’t actually false, it just needs to be applied depending on the particular circumstances. While it is true that “3-6 minutes of stretching reduces passive resistance up to 1.5h” (6), that’s only to say that after a classic RG warm-up, your gymnasts will stay at their most flexible state probably for the rest of the training, which is ideal. What can create a problem is that 5-minute window Mrs. Moltubakk talks about in her webinar, which, after static stretching, decreases power and speed. However, that only applies to situations when you need to perform dynamically immediately after. The same has been concluded by a number of studies with a consensus that less than 60s of static stretching will not have a negative effect on dynamic performance or strength (14). Furthermore, short static stretches during warm-up have been shown effective for muscle and tendon injury prevention which is crucial in our sport, as well as probably all others. Therefore the take away is - at a competition right before your gymnast is going to perform, rather than pushing her into splits, you should be focusing on quick conditioning, dynamics, and reflexes, however, in day-to-day practice, you don’ t have to worry about longer stretching impairing your gymnasts’ performance at all.

How to apply these findings into training:

Now you know you don’t have to worry about losing your flexibility or your strength if you combine the two. The gains in either area will depend on many factors, most noticeably on your natural physical state – if you’re hypermobile, you’ll need to increase your strength training volume and vice versa – if you’re tight and dynamic, you’ll have to do more stretching. The bigger the difference in your performance in either area, the longer it will take to balance them out – but the point is it is possible. However, it is important to know when to do which exercise and how. Because we need to be able to use our strength in elements with high amplitude, the way we strengthen and condition isn’t going to be the same as that of an artistic gymnast or a cheerleader.

- Combine the two

To achieve strength in flexibility elements and master the body difficulty, we need to develop active flexibility / the strength within extreme overstretched movements. With that in mind, we need to organize our training in way that ensures that these 2 components don’t cancel each other out. Easy way to show this:

- 1. Cardio / endurance training (running, rope skipping) alternated with plank variations

- 2. Warm-up (making sure each exercise contains both components – strength and flexibility)

- 3. Oversplits (lifting and relaxing hips, use different positions, add apparatus handling)

- 4. Break (here’s the 5-min window to regain their strength)

- 5. Dynamic stretching and balance practice (first kicks and waves by the bar, then transfer it on the floor)

- 6. Leaps and acrobatics (alternate jumps and leaps with rotations and acrobatics for better balance and proprioceptive ability)

- Weights and resistance

First of all, I hope none of you still believe that weight training or excessive training will stop a child from growing but let’s address it just in case. Since 2011 a final consensus has been reached by scientific community and FIG (International Gymnastics Federation) that gymnastics does NOT slow down maturation or growth (15). The theory only existed because all the studies conducted on the topic were observational - meaning they saw that gymnasts were shorter and often had a later onset of puberty so they concluded it was due to gymnastics, either blaming high training volume or weight lifting. The truth is there is no evidence to show that hard training has anything to do with this. If a female gymnast is shorter (which is usually the case for artistic gymnasts), her stature is actually a reason why she was scouted and why she’s had a successful career because the smaller you are, the easier it is for you to tumble and control your body in general. Regarding the other issue – late maturity – gymnastics can be at fault indirectly by putting a lot of pressure on girls to stay skinny, for both performance and perceived elegance, which more often than we’d like, results in excessive dieting restrictions or even eating disorders which in the end, can be a culprit for their late maturation. However, the training itself, using weights or resistance, is actually quite beneficial.

The myth that female gymnasts shouldn’t lift weights has been debunked already in 2000 when researchers from the US made a clear distinction between weight-training styles – either maximizing or minimizing hypertrophy, the muscle growth; and the fact became well-known to general public. The fear both artistic and rhythmic gymnastics coaches may have is that of bulking up their gymnasts if they use too much weight or an inappropriate training technique. This concern can be easily set aside if we delve into the mechanisms of weight training. This review article in Sports Science from 2000 explains the issue very simply: For maximizing hypertrophy, we need to increase the number of repetitions, train with light weights, and only allow quick rest times in between the sets (1-3 min). For minimizing hypertrophy, we should use heavier weights, do a smaller number of repetitions, and let our gymnasts rest in between sets (up to 5 min) (16). With rhythmic gymnastics in mind, we’re not going to use 50kg weights and do bench presses; the idea is to use the heaviest weight your gymnast can effectively work with using proper technique while it is still challenging. I usually start using ankle weights around the age of 8 and only use the weight that corresponds to the particular gymnast’s ability – we can start with 300g, go to 500g, and then use the 300g ones on her wrists. One thing to stress here is that ankle weights should be used during warm-up (point 2 through 5 in my schedule above) and not for jumps and leaps in order to prevent injuries that could easily happen when your gymnast is already tired and isn’t fully aware of the added difficulty.

Next, resistance training has been shown very effective in developing strength while minimizing hypertrophy. Because a large amount of exercises using resistance bands target the deep stabilizing muscles, this kind of training improves balance while the size of the muscle remains unaffected. During these exercises gymnasts have to concentrate on the right technique and consciously activate the muscles in order to keep their balance and perform the particular exercises correctly, which creates more awareness and subsequently improves their coordination. It’s widely accepted that resistance training is not only safe but beneficial for development in young athletes, and also serves as a preventative measure in professional sports (17). In a rhythmic gymnastics-specific study from 2014, Italian scientists performed an experiment on pre-junior and junior aged rhythmic gymnasts to find out the effects of two different types of resistance training on their jumping abilities. In one group they used dumbbells and for 6 weeks the girls were doing a generalized training, while the other group was assigned an RG-specific training plan using weighted belts. After the experiment, they tested the subjects’ jumping ability using 3 kinds of jumping techniques – a vertical jump starting in a squat position, a vertical jump with counter-movement, and a hopping test, assessing their legs’ explosiveness and jump height. They also measured their active flexibility by having them perform basic hip movements with square hips / keeping the pelvis steady. Both groups improved their jumping ability / explosive strength by 6-7%. The generalized group got better results in the hopping test which could serve as an indication to train classic plyometric exercises especially for jumps like the butterfly or switch leaps to improve gymnasts’ power and speed. However, the researchers concluded that RG-specific resistance training is preferable because in this case as well as in several other studies, it improved the gymnasts’ “reactive strength.” Therefore, in most cases, especially when working with very flexible gymnasts who focus on the less dynamic and more flexible leaps (all kinds of slow split leaps with take-off from 1 leg, especially with bent trunk) where they need to “pull the legs up” in an elegant motion, coordination and specific strength is more important. As in both groups, gymnasts’ thighs grew a few centimeters (which is undesirable in RG), to avoid this, the researchers advised to use weighted belts at a maximum of 2% of athlete’s body weight (17) – so if you do what we do, taking your 300-500g ankle weights and sticking them on over your waist during jumping series, you’re doing it just right.

Lastly, but certainly not least, I would like to mention BOSU ball workouts. Since I got one on Christmas in 2014, I have fallen in love with it and never stopped using it with my gymnasts. There are a number of very similar products nowadays on the market, lots of balance boards and cushions but those are usually quite advanced for small gymnasts, thus ineffective. If you want to strengthen your gymnasts’ ankles, which you must do for every future relevé balance and stability during routines, BOSU balls are the perfect tool for it. First, you should start with basic front passé balances on flat foot, basically forcing your gymnasts to find their balance and then start incorporating all the shapes of body difficulty they routinely use in training and advance with the ones you want them to learn. The spike of improvement is amazing! I’ve had girls do relevé balances on BOSU ball for 1 minute in 2 weeks after we started using them. We made it harder by incorporating apparatus handling during the balances and the results were outstanding. If I could give you 1 advice that I swear by, this would be it..

What about the older girls?

It is widely agreed by scientists that flexibility decreases with age but how quickly and by how much? A Canadian study from 2013 tested 436 subjects ranging from 55 to 86 years old and found out that both genders were slowly losing flexibility. Relevant to RG, women registered a 7° decline in their hip flexibility in 10 years beginning at 63 years of age (as opposed to men with 6° per 10 years starting at 71!). The sad part is that physical activity played almost no role in this decrease in flexibility (19) meaning that even if you do stretching until you’re old, there’s still going to be a slight decrease that cannot be affected. However, most people reading this (and their children) are probably not 63 yet AND even if you are, you can probably still improve your flexibility from the point where you are now. There really isn’t enough research on the topic of increasing flexibility during different lifetime stages but we know that when babies are born, their hip mobility is the highest and as they grow, this range of motion slowly decreases up to puberty due to their growth plates closing up and from that point on, there is no non-invasive way of increasing the joint mobility (15). However, if gymnasts’ hips aren’t one of the most flexible ones, you can still possibly alter their development by starting stretching training very soon. That’s one of many reasons why both artistic and rhythmic gymnastics coaches start their courses at the age of 3-4, sometimes even earlier with those “mommy and me” classes. However, regardless of your flexibility level, even after puberty you still have your own limit you can reach without chronic impairment so if you do have flexible hips and spine, you can still become flexible as an adult just by stretching and strength training properly – so don’t be discouraged if you think you’re too old for this. As cliché as it may sound, whatever your age, you absolutely CAN reach your full potential. Just don’t compare yourself to others because everybody’s body is different and here it’s doubly true. Do your best and remember: It’s only as difficult as you think it is.. ;)

References:

- NHS Inform, 2021: Joint hypermobility. (https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/muscle-bone-and-joints/conditions/joint-hypermobility). Retrieved Jan.30, 2021.

- Science of flexibility, Michael J. Alter, MS., 1952. (https://books.google.sk/books?hl=sk&lr=&id=3pPAWd1PW2sC&oi=fnd&pg=PP12&ots=6prIJjvUXc&sig=RCAHVmS51kGigAJkMrq1sJs-xLo&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false). Retrieved Feb.21, 2021

- Physiopedia, 2021. Benign Joint Hypermobility Syndrome. (https://physio-pedia.com/Benign_Joint_Hypermobility_Syndrome?utm_source=physiopedia&utm_medium=related_articles&utm_campaign=ongoing_internal). Retrieved Feb.21, 2021.

- Current Sports Medicine Reports, originally by: American College of Sports Medicine, 2013. Joint Hypermobility and Sport: A Review of Advantages and Disadvantages. (https://journals.lww.com/acsm-csmr/Fulltext/2013/09000/Joint_Hypermobility_and_Sport___A_Review_of.7.aspx). Retrieved Feb.21, 2021.

- Disputas NIH, 2019. Marie Moltubakk – Ph.d. dissertation January 15th 2019. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2i5srQJvg-I&ab_channel=DisputasNIH). Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- Mamoltub, 2020. The science of flexibility and stretching in rhythmic gymnastics, part 1 (continues to part 3). (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gm_0wMWKhY4&ab_channel=mamoltub). Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- Maria Khoreva, 2021. VAGANOVA vs ROYAL (Ballet Academy & School) Maria KHOREVA & Claudia DEAN. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=03bLS3ynr0U&ab_channel=MariaKhoreva). Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- Solodance.eu, 2021. BACKWARMER FOR RHYTHMIC GYMNASTICS SASAKI HW-8043 BLACK SIZE JF (JM~JL) (105~137 CM). (https://solodance.eu/catalog/oblecenie_na_zohriatie/ohrievaci_pas_na_modernu_gymnastiku_balet_jogu_sasaki_hw_8043/?offer=4452). Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- Unizdrav.sk, 2021. Termoelastický ľadvinový pás DAVID. (https://unizdrav.sk/tovar/963/termoelasticky-ladvinovy-pas-david). Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- University of Maryland Medical Center, 2021. Spondylolysthesis. (https://www.umms.org/ummc/health-services/orthopedics/services/spine/patient-guides/spondylolisthesis). Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- Robert H. Schmerling, MD. Harvard Health Publishing. Harvard Medical School, 2021. Posted May 14, 2018, updated October 27, 2020. Knuckle Cracking: Annoying and harmful, or just annoying? (https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/knuckle-cracking-annoying-and-harmful-or-just-annoying-2018051413797). Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- Olympics, 2020. Anatomy of a Rhythmic Gymnast: How Strong is Ekaterina Selezneva? (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8LFHLJuTM_E&ab_channel=Olympics). Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2021. Leite, et.al., 2015. Influence of Strength and Flexibility Training, Combined or Isolated, on Strength and Flexibility Gains. (https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/fulltext/2015/04000/influence_of_strength_and_flexibility_training,.31.aspx). Retreived March 16, 2021.

- Frontiers in Physiology, 2021. Chaabene, H., Behm, D. G., Negra Y., Granacher U., 2019. Acute Effects of Static Stretching on Muscle Strength and Power: An Attempt to Clarify Previous Caveats. (https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2019.01468/full). Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- FIG Education Channel, 2020. Training for a growing child. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DA2-jUG84vo&ab_channel=FIGEducationChannel). Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- Sport Science, 2021. Sands, W.A., PhD, and others, 2000. Should Female Gymnasts Lift Weights? (http://sportsci.org/jour/0003/was.html). Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- Researchgate, 2021. Italian Journal of Anatomy and Embryology, 2014. Effects of resistance training on jumping performance in pre-adolescent rhythmic gymnasts: a randomized controlled study. (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264859118_ITALIAN_JOURNAL_OF_ANATOMY_AND_EMB_RYOLOGY_Effects_of_resistance_training_on_jumping_performance_in_pre-adolescent_rhythmic_gymnasts_a_randomized_controlled_study_Key_to_abbreviations). Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- Orrison, W. W. Jr., Perkins, T.G., 2009. Dynamic whole-spine MRI of contortionists. (http://incenter.medical.philips.com/doclib/enc/fetch/2000/4504/577242/577256/588821/5050628/5313460/6172193/08_Orrison_Vol_53.pdf%3fnodeid%3d6176308%26vernum%3d-2). Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- NCBI, 2021. Journal of Aging Research, 2013. Flexibility of Older Adults Aged 55-86 Years and the Influence of Physical Activity. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3703899/). Retrieved March 18, 2021.